Isn’t it really just learning by another name?

We hear a lot about knowledge building in education circles these days!

What is it anyway? Why don’t we just call it learning? Where did this term knowledge building come from?

When I first started speaking of knowledge building (KB), people looked at me as if I had two heads! People thought the term to be officious and puffed-up. But, now—now it’s ever-so-cool. Everyone is using it—but, perhaps without any deep understanding of its roots, its meaning—beyond that of learning. In fairness, this is actually a fairly common phenomenon as new concepts and words come into our everyday lexicon. It is known as lexical or semantic drift. Meanings change from the original intent.

So it is with knowledge building.

The purpose of this article is to briefly familiarize readers with the origins and intended meaning. Links to other sites and articles will help to broaden and deepen your understanding of the complexity of knowledge building, of creating knowledge building communities and of KB technological environments. It certainly won’t all be explained here! 😉

Learning vs Knowledge Building

This graphic (courtesy of IKIT) delineates the conceptual differences between learning and knowledge building.

A Little History

The origins of knowledge building in education arise out of the work of Marlene Scardamalia and Carl Bereiter at OISE/UT. Their work in knowledge transforming and intentional learning—as it relates to the development of expertise—has been the foundation of their coining the term knowledge building. This work goes back to the mid 1970s and their development of CSILE—Computer Supported Intentional Learning Environments in the mid 80s.

People often equate knowledge building theory with that of constructivist learning, but Scardamalia and Bereiter make these distinctions:

Intentionality. Most of learning is unconscious, and a constructivist view of learning does not alter this fact. However, people engaged in Knowledge Building know they are doing it and advances are purposeful.

Community & knowledge. Learning is a personal matter, but Knowledge Building is done for the benefit of the community.

In other words, students engaged in knowledge building are intentional about their learning—they treat knowledge as an entity that is discussable. It is something about which they reflect and build upon. Also, students can be said not just to be in charge of their own learning, but also have responsibility for the learning of the group.

1977-1983: Knowledge-Telling versus Knowledge-Transforming

As described in detail in A Brief History of Knowledge Building (pdf), between 1977-1983 the research focus was on examining the differences between knowledge-telling and knowledge-transforming. So when you are using wikis with students for collaboration and knowledge-building, ask yourself, “When students post information on their various wiki pages, are they simply telling knowledge or are they transforming that knowledge by thinking about it, questioning it, reworking it, combining it with other pieces of information to make new understandings and revelations?”

I describe here a situation where true collaboration occurred between two students (visible to all students) in which the questioning by one student (Heather) led the other (Larissa) to rethink and to rework her driving question for her project on potato production in Prince Edward Island. She needed to do more than knowledge telling. She was required to build new schema by a deeper transformation of the information at hand.

1983-1989: Intentional Learning

Between 1983-1989 the research focus switched to intentional learning and cognition. “Intentional cognition is something more than ‘self-regulated learning’, more like the active pursuit of a mental life.” Intentional learning had several characteristics which pointed towards knowledge building. These included:

- Higher levels of agency. Students take responsibility not only for meeting learning objectives set by the teacher but for managing the long term acquisition of knowledge and competencies.

- Existing classroom communication patterns and practices as obstacles to intentional cognition. Even though teachers may try to encourage inquiry and independent learning and thinking, common characteristics of the classroom environment militate against it and instead increase dependence on the teacher (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1996).

It was during this time that CSILE was developed. Originally, it was a text-based system and I, personally, was challenged by a text only environment—as I was a recent HyperCard enthusiast and enjoyed, and saw cognitive benefits for, graphical interfaces and hypermedia. As part of the CSILE team, I made a case for multiple representations of knowledge—beyond text only.

This was a time rich in studying expertise, the differences between expert and novice behaviour and, indeed, how one encourages and supports the development of expert learners—both face to face and in online spaces. Protocols and procedural facilitations were developed to scaffold the execution of higher level strategies by students.

It was recognized, as we hear so much now, that teachers may indeed be a bottleneck in the advancement of knowledge creation by students. However, it’s not merely about student agency—that is necessary, but not sufficient. Students must learn the skills, develop the attitudes and build/participate in the community.

1988-present: Knowledge Building

As the research into intentional learning developed, the researchers noticed something else happening in the CSILE classrooms that involved all the students. They noticed that the kids became really involved in contributing to the knowledge problems that arose. In fact, to be part of the classroom community, you really needed to contribute. So it seemed that a great motivator and sustainer of intentional learning behaviour was ‘the simple and virtually universal desire to belong’.

“This conceptual step yielded a definite separation between intentional learning and Knowledge Building. Intentional learning is the deliberate enhancement of skills and mental content. Knowledge Building is the creation and improvement of knowledge of value to one’s community. You can have intentional learning without Knowledge Building and, in principle at least, Knowledge Building without intentional learning; but the two together make a powerful combination.”

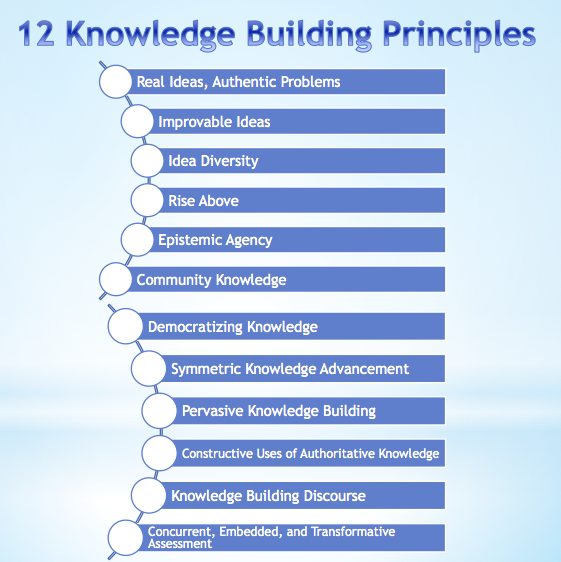

Twelve knowledge building principles have been articulated. I will mention them here, but I suggest you read the complete descriptions or watch these videos because the headings won’t tell you too much! I include them in this graphic to illustrate the depth and complexity of the term knowledge building.

Knowledge Forum

Knowledge Forum evolved out of CSILE and is available to support you in developing knowledge building classrooms.

Here is a brief video from a classroom using Knowledge Forum. (Note: This is fairly old—the technologies have improved! But, great overview!)

So in summary…

One cannot equate learning with knowledge building.

The terms are not interchangeable and I believe we need to be careful when we appropriate language and use it casually. I have the same concern with other current, common constructs such as inquiry, collaboration, and project-based learning.

I am absolutely certain that I do the same thing with many expressions and terms where that domain is not my area of expertise!

Please be patient with me when I do so, but please also gently point me to resources that will deepen my understandings.

Call to Action

Given the topic of this post, I will now ask you to do a little reflection on the ideas presented here, on your previous and current thoughts about learning versus knowledge building, on your own practice, and on the dominant classroom and school culture in relation to these ideas.

- What have you learned?

- What might change for your practice?

- What steps might you take to move forward?

- What confusions/questions do you have?

I encourage you to do this publicly—here or in another online space where we might further our collective understandings.

Resources for Follow-Up

A Brief History of Knowledge Building: A Brief History of Knowledge Building is a great place to start reading about knowledge building.

Knowledge Building: Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2003). Knowledge Building. In Encyclopedia of Education. (2nd ed., pp. 1370-1373). New York: Macmillan Reference, USA.

Professional Development: Knowledge Building: The Professional Development: Knowledge Building site is a superb site developed by the OISE originators. Find out what a knowledge building classroom looks like, how to get started, assessment strategies, etc.

IKIT (Institute for Knowledge Innovation and Technology): “The Institute for Knowledge Innovation and Technology conducts research, develops technology and helps build communities aimed at advancing beyond “best practice” in education, knowledge work, and knowledge creation.”

Knowledge Forum: Knowledge Forum is available for purchase and implementation in your school or classroom.

Natural Curiosity: Natural Curiosity is a resource that has been developed for teachers. There are wonderful classroom videos online describing ideas about developing a knowledge building culture and knowledge building discourse among students. You can also download a Natural Curiosity handbook.

Learn Teach Lead: LearnTeachLead, of the Ontario Ministry’s Student Achievement Division, has produced and posted some excellent videos including interviews with Marlene Scardamalia.

Visible Thinking: I would also recommend the book, Visible Thinking, by Harvard’s Project Zero group. The Visible Thinking website also has some worthwhile resources.

ThinkingLand: In the mid 80s, as a graduate student in the CSILE group, I developed a networked version of HyperCard called ThinkingLand. It was based on the metaphor of a journal and so could be considered as an online, collaborative, and scaffolded journal writing environment. It was implemented in a sixth grade classroom for research purposes.

Journal Zone: In 2000, LCSI (of Logo fame!) contracted me to lead the design of Journal Zone—which was based on ThinkingLand. It was an awesome online environment, but was not commercially successfully as it launched just at the same time as blogging arrived on the scene. People went blogging—without all the scaffolding and procedural facilitations we had built into Journal Zone. (It is no longer available.) See Using Visible Thinking Strategies to Develop Expert Learners for a description of the practical elements of Journal Zone which you can build into your classroom practice.

First posted at Big Ideas in Education and at Inquire Within

So there is ‘learning’ in knowledge building, but there is no necessarily ‘knowledge building’ in all learning? This reminds me ‘collaborative problem solving’ project run out of University of Melbourne (http://readwriterespond.com/?p=36) where they spoke again and again on true collaboration as being authentic and not contrived.

I think that what is really interesting is that like Inquiry etc … it is not something that can simply be turned on for a special subject (http://readwriterespond.com/?p=592).